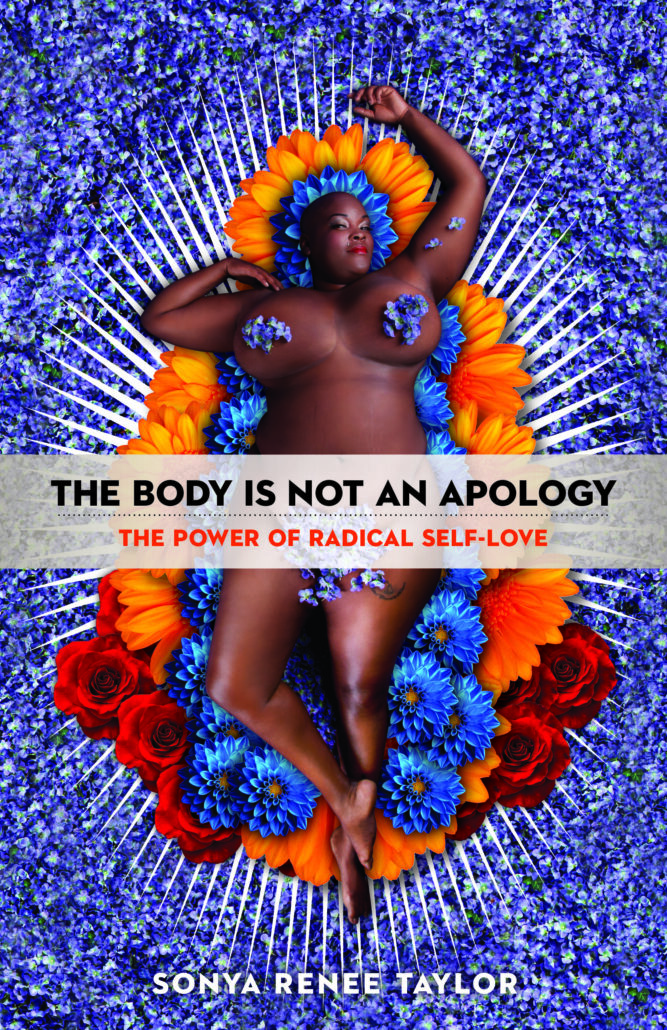

How does it feel to read these words: your body is not an apology. Sonya Renee Taylor, writer and activist, has said just that, and asks the question, what might it feel like to embody radical self-love? When I first read that sentence on the cover of the book, I had two reactions. My body screamed YES! My mind and heart felt triggered. The YES was the radical (meaning fundamental, as in the definition: of or going to the root; fundamental) acknowledgement of self-love for my divinely made self. The trigger, however, was the profound realization of how often and for how long I’ve been apologizing for this self.

Here’s an example: The shape of my Roman hooked nose is one of a few physical features I was mercilessly teased for as a middle- schooler. In today’s terminology, this would be called bullying. I thought for sure there was something wrong with me, though, and not something wrong with the act itself. So I grew up into a 40-something woman who made sure to stand in such a way that no one saw me from my profile. Oh Sonya Renee Taylor, how convicting your message. I realized how very sorry I’ve been for having this nose, that I didn’t want to impose my profile on anyone else. That act–standing just so–was my apology to the world for the shape of my nose.

This year I decided to stop apologizing and start adorning lovingly. On my daughter’s 14th birthday, she treated herself to three new piercings in her ears, while I treated myself to a nose piercing. If you’d have asked me on my 36th birthday if I’d ever pierce my nose, I’d have stated an adamant, “no way” for why on earth would I want to draw attention to my nose?! Here I am, 10 years later, with what feels very much like a symbolic act of radically loving and accepting me–all of me, exactly as I was made to be. It was an act of radical freedom.

Why does this matter in terms of the longtime history of large scale bodily oppression and injustice? How can this act of freedom potentially affect my global community? Sure it could seem like this is just about my nose, small scale when considered in terms of larger scale body injustices. Yet, how has the shame I enact on myself reinforced a larger current of shame?

Taylor writes, “We can’t help but be heartbeat present to the fact that our relationship with other bodies mirrors in tangible ways our relationship with our own body. Yes, we have been cutting and cruel to ourselves and have watched our internalized shame spill over into how we parent, how we manage employees, how we show up to friends and family. Yes, we believed that our bodies were too big, too dark, too pale, too scarred, too ugly, so we tucked, folded, hid ourselves away and wondered why our lives looked infinitesimally smaller than what we knew we were capable of.”

Living the small life, keeping others in a position of needing to hide themselves away, tucking and folding myself and others into an image of what it means to be “healthy,” “strong,” “beautiful,” have all been ways of deciding something bigger–what it means to be worthy in this world of being seen.

Taylor includes multiple moments throughout the book to pause and reflect. She calls these “unapologetic inquiries.”

In one she asks, “Who in your life is most affected by your body shame? How is it impacting them?”

So I ask myself some unapologetic inquires with hard answers. What thread of shame have I kept woven into the human fabric, reinforced with my own threads? And who is that person most affected by my body shame? Maybe my daughter, maybe my husband, maybe my son. Maybe women and men I don’t even remember. I don’t know for sure, but I believe without a doubt that the thread of shame stays woven until the relationship we have with our own body becomes one that is examined and held in love. And that thread of shame–it’s the thread that keeps us willing to abuse and slaughter and maim ourselves and the beautiful bodies of humanity. I am convicted, and as Maya Angelou says, “When we know better, we do better.” It’s time for humanity to both know better and do better. I guess I have a bit of an agenda here–I hope everyone heeds this as a call toward radical self-love. Read the book. Engage in some unapologetic inquires. Praise your body, for you need never repent for the beautiful being you are.

From the poem, “The Body Is Not An Apology,” by Sonya Renee Taylor

The body is not to be prayed for, is to be prayed to.

So, for the evermore tortile tenth grade nose,

Hallelujah.

For the shower song throat that crackles like a grandfather’s Victrola,

Hallelujah.

For the spine that never healed, for the lambent heart that didn’t either,

Hallelujah.

For the sloping pulp of back, hip, belly,

Hosanna.

For the errant hairs that rove the face like a pack of Acheronian wolves.

Hosanna,

for the parts we have endeavored to excise.

Blessed be

the cancer, the palsy, the womb that opens like a trap door.

Praise the body in its blackjack magic, even in this.

For the razor wire mouth.

For the sweet god ribbon within it.

Praise.

For the mistake that never was.

Praise.

For the bend, twist, fall, and rise again,

fall and rise again. For the raising like an obstinate Christ.

For the salvation of a body that bends like a baptismal bowl.

For those who will worship at the lip of this sanctuary.

Praise the body, for the body is not an apology.